I have just made an interview with the author John Higgs for my BUREAU OF LOST CULTURE radio show. John’s book ‘Stranger Than We Can Imagine - Making Sense of the 20th Century’ is a terrific read - it really provides a narrative to understand a radically changing world and the birth of the youth culture. We mainly talked about the emergence of the teenager in the post war years. John places ‘teenage year zero’ to the 1953 issue of ‘Tutti Frutti’ by Little Richard.

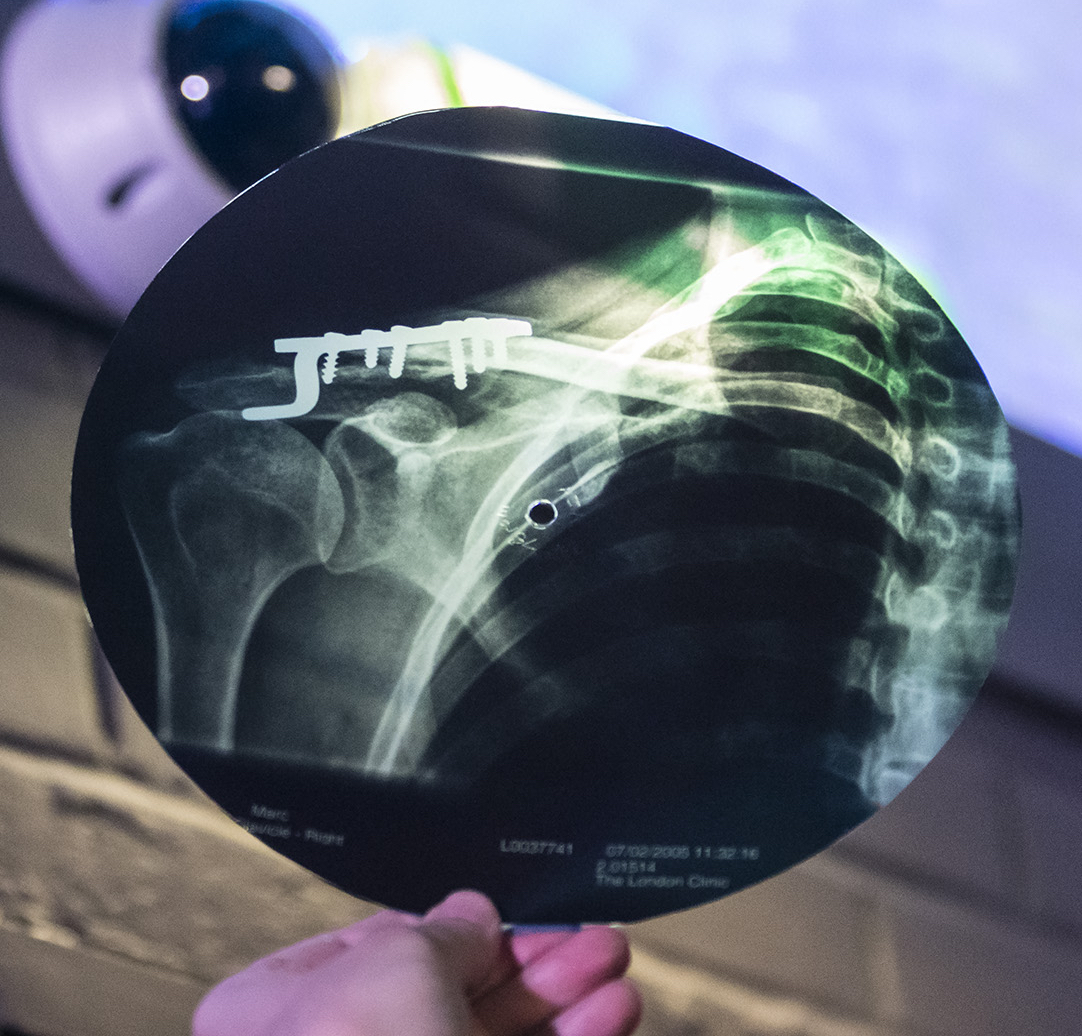

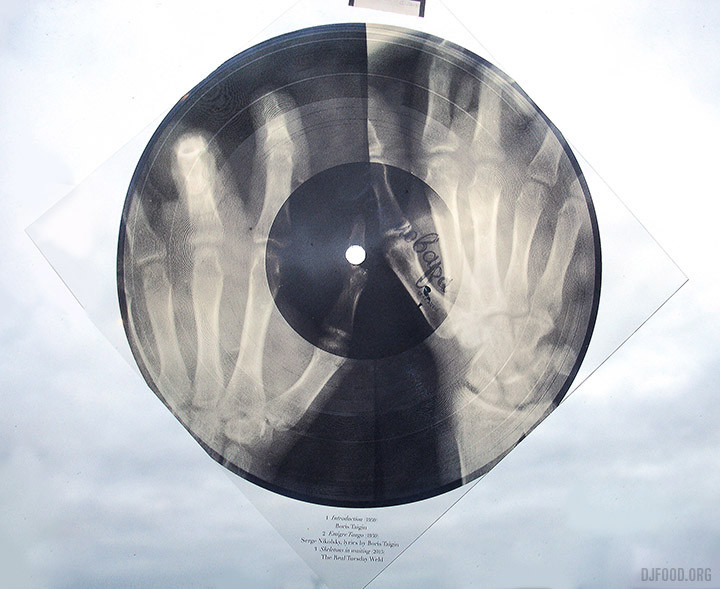

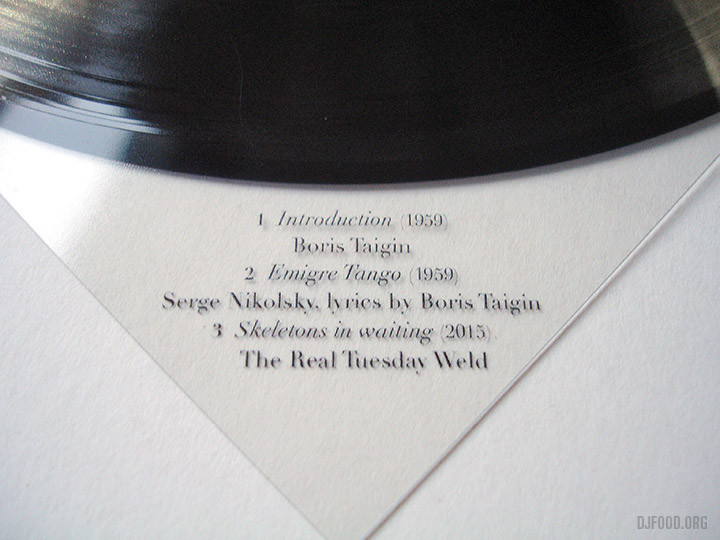

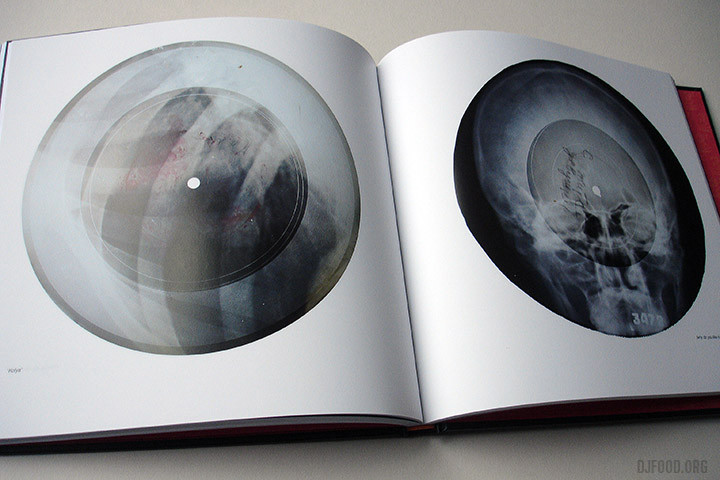

Tutti Frutti, along with Rock Around The Clock, ignited teenagers on both side of the iron curtain and one of the things that has been interesting in researching our new book Bone Music is seeing how the ‘youth quake’ of the US and the UK spread through the Eastern bloc powered by swing and rock’n’roll. It is also fascinating to realise that the X-Ray underground, which serviced those styles to young Soviets, was itself a teenage phenomena - particularly at the beginning.

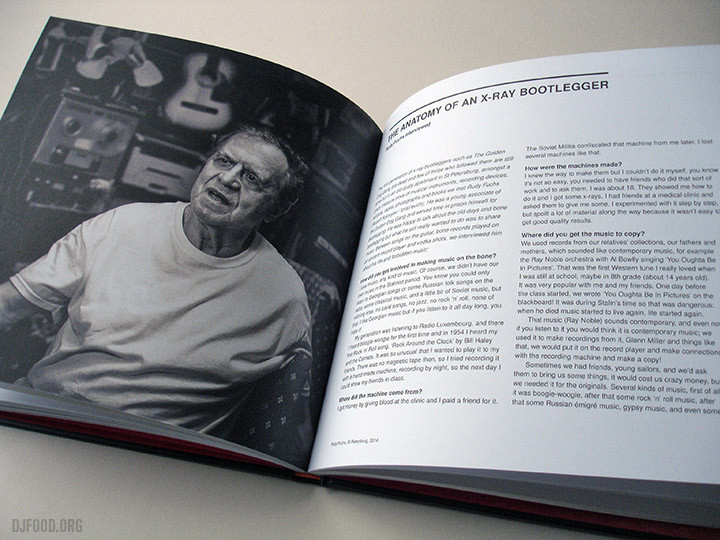

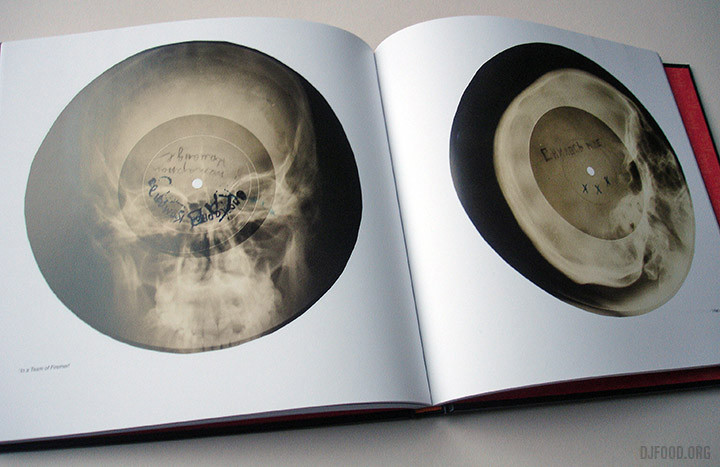

Boris Taigin and Russian Bogaslovsky, started cutting Bone Music as the Leningrad bootleg outfit The Golden Dog Gang when they were only 18. Mikhail Farafanov, another of our interviewees, when he was just 17. Most of their customers were teenagers too. Kolya Vasin was barely 14 when he first came across Little Richard on an x-ray record. It blew him away. His friend came to his house after school and showed him a disc saying:

‘Look Kolya! This is American rock’n’roll!’

He took the record in his hands, looked at it through the light and saw the image of bones. Immediately, he was fascinated and, when he put the record on the gramophone and it started spinning, he heard wild singing. He was delighted by the ecstatic screaming voice, and fell back, stupefied.

‘Who is this!?’

His friend said it was Little Richard and the song was ‘Tutti Frutti’. Kolya immediately became a convert at the church of rock’n’roll.

I have written several times about the Stilyagi, the only real Soviet youth culture group according to Artemy Troitsky. These were kids who listened to rock’n’roll, jived, drank, tried to dress how they imagined American kids did, spoke in pseudo American slang and generally wanted to have fun. I discovered there were similar groups in most of the Eastern bloc countries: Hungary had the Jampecek, in Poland there were the Bikiniarze, in Czechoslovakia the Potapka and in Romania the Malagambisti. All dressed in an ersatz rock’n’roll style and aped US mannerisms.

Like their western counterparts, and the earlier French ‘Zazous’ and German ‘Swingjuden’ (swing kids), they all used music and clothes to distinguish themselves from the older generation and from their more conventional peers who reacted with shock and confusion. The media and the authorities were enraged - just at they were in the West at the British Teddy boys and the US rock’n’rollers.

The similarities across these various groups were remarkable. A pamphlet publicised by the British Anarchist Federation described how a fascist magazine in wartime France wrote of the the male Zazou

”Here is the specimen of Ul-tra Swing 1941: hair hanging down to the neck, teased up into an untidy quiff, little moustache a la Clark Gable,..... shoes with too thick soles, syncopated walk”.

Female Zazous wore their hair in curls down to their shoulders or in plats. Blonde was the preferred colour worn with bright red lipstick, and sun- glasses, jackets with extremely wide shoulders and short skirts. Stockings were striped or fishnet, worn over shoes with thick soles (see images)

It is virtually an exact description of the eastern bloc cold war kids - who were just a little later to the party. The fascist youth movement the Jeunnesse Populaire Française patrolled the streets with scissors, attacked zazous and forcibly cut their hair - just as the Soviet youth patrols Komsomols did to the Stilyagi, Even the satirical cartoons published by a disparaging media were a dead ringer. Yet all these groups were small in number - often just a few in any town.

But teenage styles change - and fast. The stilyagi fell behind the times, partly because fashions had moved on in the west and partly because they were growing up. New generations of teenagers caught the bug of clothes, dancing and cool music and in the more open climate of Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’ were forming their own youth culture, dismissive of the previous generations’ style - just as they always have been.

A fascist paramilitary forcibly cuts a Zazous’ hair.