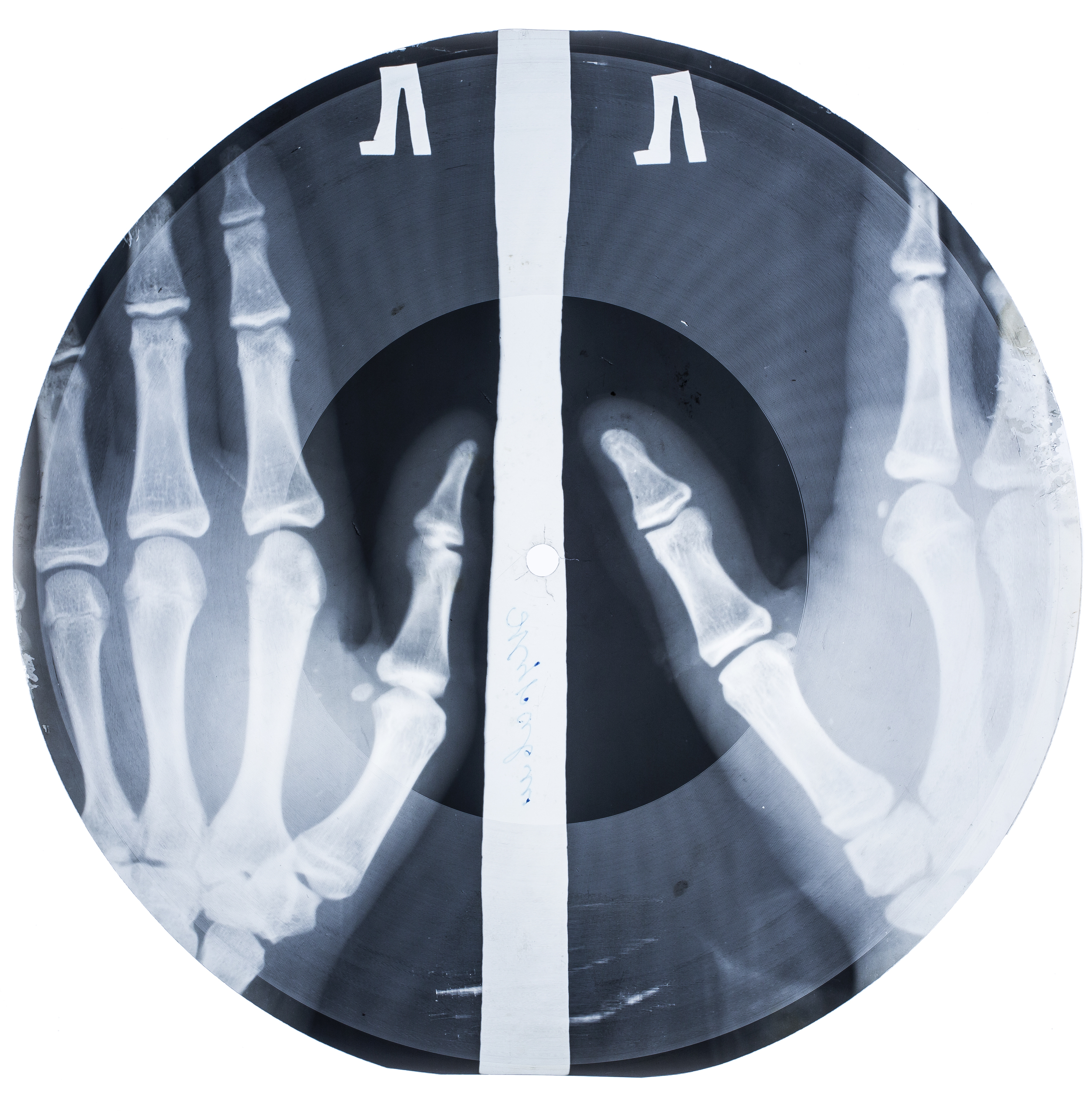

Courtesy Justinas Shimkauskas

In the Soviet Union in the years after the second world war, a lot of music was banned. Almost everything Western was forbidden because the USA and Britain in particular had become seen as the enemy and their culture was held to be harmful. But a lot of Russian music was also forbidden. Anything made by emigres was off limits because by definition, any Russian who had wilfully left the country or who stayed away by choice was now considered a traitor - whatever their repertoire and even if they had previously been approved of. Some of these people had been huge stars before the war. And what is perhaps more difficult to comprehend, is that a lot of domestic music made by Soviet citizens was also forbidden, or at the very least deemed 'unofficial'. Why?

(continued beneath)

To listen to more Bones records go here.

From 1932 and especially during the Stalinist era, all Soviet art, literature, poetry, film and music was controlled. The ideologues of the Soviet Union believed passionately in culture but also that all art had to be in the service of Socialist Realism and support communist ideals. And therefore it must be subject to an official censor. Self expression was out. Many Russian popular tunes, especially those from the folk tradition called 'criminal' songs, whilst not really anti-Soviet in themselves, were deemed to be 'low culture' and would not pass these conditions. Many of them were songs that had become popular in the gulags. Like a Jacques Brel track, they might be songs about violence or jealousy or about the rough and tumble of love and lust and life in the camps. A Russian friend said to me recently: "Remember, at that time, every family had at least one member in the gulag..". And even certain rhythms such as the foxtrot were banned on the basis that they might lead to wild, licentious behaviour, late night gatherings and general frivolity.

But young hearts were beating. People had a huge pent-up desire to hear their own music: songs which they had heard in the gulag or sung by those who had returned; songs which they had loved in previously, less controlled times; songs by artists who were now persona non grata and even perhaps songs that they had heard played by some local singer at a clandestine concert. And of course, there was a demand for the impossibly exotic seeming Western music, the Rock and Roll or Jazz which might be caught on an overseas radio broadcast the state hadn't been able to jam or heard at a party on gramophone records smuggled into the country by merchant sailors or diplomats. Such records would be rare and fabulously expensive, costing the equivalent of a month's wages. This combination of huge demand with restricted supply is of course the perfect condition for a market to arise. And true to form, into this market, into this gap between supply and demand stepped the bootleggers.

We had our own bootleg culture in the West once - live recordings of concerts by the big Rock gods made on vinyl or tape in the days before the internet changed everything. But even if illegal, these were relatively easy to make. In the Soviet Union during the period from the late forties to the early sixties, it was not so easy. The bootleggers' first technical problem, that of obtaining a machine to record with was relatively straightforward. Literature existed explaining audio recording techniques (say in case a righteous citizen wanted to copy the speeches of Comrade Stalin) and various recording machines had been brought back from Germany as trophies after the second world war. These could be adapted or copied, but a further problem existed. The State completely controlled the means of manufacturing records. You couldn't just go and buy the vinyl or shellac or lacquer needed in a store somewhere.

But at some point, some enterprising music lover hit on a genius idea. An alternative source of raw materials was available - used X-ray plates obtained from local hospitals. And that is where this story really begins. For many older people in Russia remember seeing and hearing strange vinyl type discs when they were young. The discs had partial images of skeletons on them and were called 'Bones' or 'Ribs' and they contained wonderful music, music that was forbidden. The practice of copying and recording music onto X-rays really got going in St Petersburg, a port where it was be easier to obtain illicit records from abroad. But it spread, first to Moscow and then to most major conurbations throughout the states of the Soviet Union.

To read a full illustrated history of the X-Ray records and the people who made, bought and sold them, see our upcoming book "BONE MUSIC’ (Strange Attractor / MIT press)

Our previous book The Strange Story of Soviet Music on the Bone is now sold out

And Contact us for more information about the project and upcoming events

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------